Revisiting Our Findings

Our study frames the journey of understanding the lived realities of non-English speakers online. In Ethiopia, India, Tanzania and Uganda, we analyzed different user groups and their experiences and sentiments on usability, accessibility and safety online. Our research probes the question: What are the lived realities of non-English speakers online? We seek to understand how languages are used and expressed in digital contexts; this research expresses the internet’s potential and its everyday, utilitarian use. We aim to create opportunities for stakeholders to work collaboratively to foster improved and interlinked relationships between developers and between users and developers.

Ethiopia is our only East African case where a non-Latin script is dominant. As a result, the separation between commonly spoken languages like Amharic and English is distinct. Platforms and software that support Amharic script, also known as ge’ez, are faulty and often do not account for nuance. Similar to other contexts, English is associated with professionalism and educational opportunity, while mother tongues are relegated to use with family members or friends. However, a sample solely drawn from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, skews our findings in a country where the majority of Ethiopians outside the capital are offline. Tanzania has a local language as its national language: KiSwahili. Yet, English is dominant online even with the prevailing government policy and investment in KiSwahili as a unifier in a linguistically diverse context. In Uganda, English as a colonial import influences Ugandans, who primarily use English online. Respondents from both urban (Kampala, Gulu) and peri-urban (Luweero) areas use English in professional settings in careers ranging from delivery drivers to farmers to students. Ugandans are especially adept at code-switching based on the audience and switching from their mother tongue (ranging from Luganda, Runyankole and Acholi to a number of the forty-odd languages spoken in Uganda) to English and back again.

India is witnessing a massive surge of users from non-urban, non-elite backgrounds due to the falling costs of data and handsets, which means that there is a large demographic coming online that is unfamiliar with English. However, despite the domination of English in online environments, users are adapting due to both the lack of accessible Indian-language resources available as well as the desire to increase their proficiency in English, as it is a significant route to economic and social mobility. There is consequently an urgency to improve upon current practices to guarantee safety, privacy and accessibility for this new wave of users.

Design Principles

What are design principles and why are they important?

Design principles are a way to formalize knowledge in order to communicate and codify innovative practices and guidelines to solve ongoing and future problems. These principles may help stakeholders with design-thinking and decision-making; they advocate for better theory, approach and practice in specific cases. Based on our analysis of language use online, we present design principles in lieu of recommendations to inform stakeholders such as web designers and developers, and also the average user affected by these design choices. We hope that they then have the ability to make well-informed design choices for a more inclusive internet.

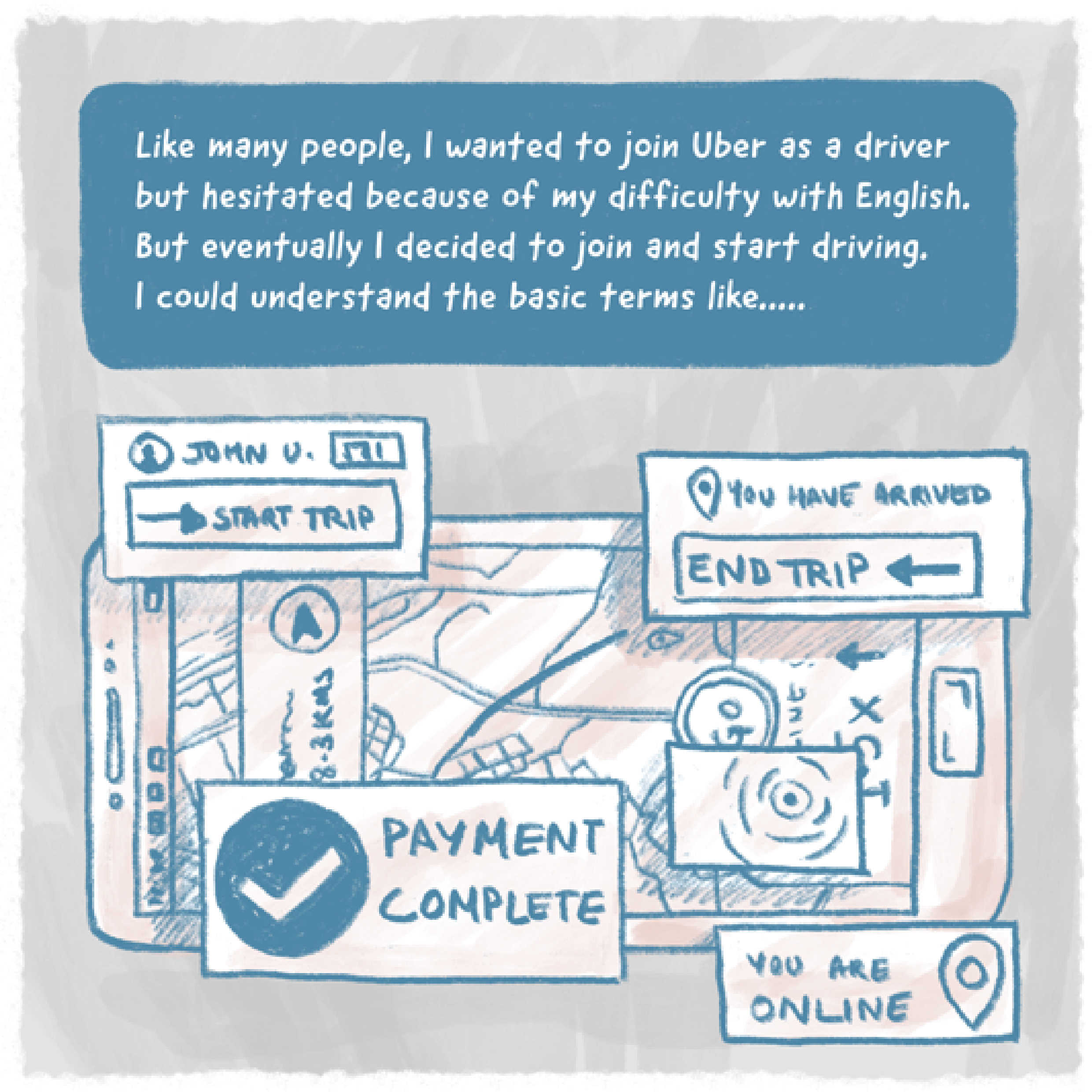

The imagining and embedding of design principles should be augmented by learnings based on user research. The following example demonstrates how a gig-economy platform in India observed how their employees use their phones for work. They focused on solving their issues based on their interactions with the employees while onboarding them on the company’s app and sharing instructional content.

| The expert interviewee explained that:

Despite a growth in their employees’ proficiency in English, whenever they encounter a complex problem, this has to be addressed in a local language. Consequently, the platform’s designers localize and transliterate concepts that require a more sophisticated understanding. The built-in help feature on the app provides local-language support as they have found that troubleshooting is more challenging for gig partners if they have to read and understand English. They are more likely to communicate in their own language with the company when lodging complaints. This means that while the company might resort to Google Translate for quick and minor changes (less than one sentence’s worth of information), they invest in human translation for anything that requires semantic understanding. In order to decrease the onus on the gig partner to rapidly parse information, the designers at the company choose to replace written instructions with animations and icons, using visual cues rather than complex copies. |

Design principles for a more equitable, user-friendly experience

We return to the themes outlined in our original research questions to create clusters of design principles.

ACCESSIBILITY ensures that more users, particularly those who do not speak English as a first language or at all, are able to use and take advantage of applications and the internet.

- Refine regional-language keyboards by understanding user patterns and the nature of the challenges they encounter. Move away from a QWERTY-based design framework for keyboards and experiment with different models for languages that have different modalities from English. For example, most Indian languages use ligatures or conjoined letters, which makes typing more complex.

- Create more applications that support multiple local or minority languages. Language inclusion should not be piecemeal but approached systematically and holistically.

- Invest in human translation as an essential rather than an afterthought. This process should also consider colloquial use and code-switching, as well as conceptual categories that are unique to a certain language. Machine translation often alienates users and can compromise context and relevance.

INCLUSIVITY dictates that the internet and related spaces accommodate non-English users and expand the information and services available for all segments of potential and current users. Inclusivity is the next step following access, to ensure users can and want to stay online.

- User research should include the discovery of what apps are considered the most user-friendly for non-English speakers and what features lend to this positive experience. In our data, this includes the ease and access of using WhatsApp over applications associated with more complex use, such as Twitter. This is easily applicable to language preference and use.

- Create opportunities to educate users on how to navigate the digital world. In low- and middle-income economies where there is great emphasis on digital-led governance to ensure inclusivity at scale, it is imperative that training, awareness and knowledge are also delivered at scale.

- Train voice recognition software to recognize local accents to ensure and increase the accuracy of voice-to-text applications.

- Support adequate user testing and explore opportunities to bring stakeholders together to inform the creation of digital products. This includes users, technology companies and the government.

- Developers and designers should work with minority language advocates and campaigners to create more technical resources in different languages.

TRUST, SAFETY AND PRIVACY ensure that internet users of all language abilities can exist online freely without the risk of harm or violence.

- Ensure that users have legible, feasible and easy-to-use mechanisms to seek help when they encounter a challenge or “pain point” on digital platforms. Guidelines, policies and other resources that are meant to guide the users’ navigation experience must be more linguistically inclusive, including meaningful digital consent.

- Encourage content moderation in low-resourced languages. Technology platforms need to invest more human and financial resources to hire and maintain content moderators in countries, particularly those with non-Latin alphabets or scripts.

- Present terms and conditions in easy-to-understand, precise and minimal language. These terms should also ideally be available as audio. This can accommodate both non-English speakers and readers, but also those with low or no literacy.

Areas for Greater Research

There is not enough research on this topic in the Global South. Our study suggests that the current steps to include more languages online are not effective. Poorly supported translation tools or a handful of applications in local languages do not replace the very infrastructure of the internet that does not support non-English languages. There should be more effort to localize content and language, especially when it comes to sourcing or adapting new words in other languages. Academics and researchers need to understand and accept that there are conceptual categories that exist in other languages that do not exist in English; this is why human translation is essential to allow us to effectively communicate certain concepts.

The study of language is a complex and multifactorial phenomenon. Researchers in this field are required to understand the issues they grapple with, both as a product of local contexts and behavioral patterns manifesting in the individual lives of respondents and as part of a broader reality shaped by social influences that are, in themselves, intricate phenomena. This includes concepts encompassing culture, identity, psychology and politics. Undertaking research at the intersection of language and technology merged two intertwined but distinct fields of study, which have garnered increasing interest. Despite the repository of a decade’s worth of research into this field, the hegemony of Global North languages – particularly English – and to a lesser extent, languages such as French, German, and recently, Mandarin, continue to dominate the literature. Fittingly, this research addresses the gap that persists around our understanding of the state of Global South languages when it comes to technology and the internet landscape.

Areas for greater research include:

Cross-sectoral engagement: There is limited research on the potential impact of greater integration of local languages online. As our research has uncovered, language integration can’t happen in a silo. Instead, it should be integrated into a reality where commensurate efforts to revitalize, protect and valorize local languages are also taking place.

Limitations for local language integration: The internet was initially conceptualized by and for English speakers. This bears implications on the extent to which local-language integration can be achieved on the internet and what that will look like. There is a need for greater research on local-language integration and expansion online.

Experience of non-English speakers: There is a connection between the frequency of internet use and literacy levels, and, by extension, the grasp of English. While our study focuses on this topic, it would be useful to broaden the scope and continue studying the online language-use practices and experiences of users with little to no ability to speak English.

Reimagined Futures

We are envisioning our collective future if and how these design principles are to potentially come to fruition. What are the implications? Does this mean people are more encouraged to read and write in their own languages and be activists for preserving their languages? We recognize that not all content online can be translated, nor is it an automatic fix to bridge the digital-language divide that is widening as more of the world’s population begins to access and use the internet.

The internet and its associated infrastructure can be reworked to explore new or creative means of language inclusion online. Users should be able to freely generate, consume and share content in their preferred language, simultaneously proliferating that language’s presence online. The average internet user is not reflective of the creators of the World Wide Web. Access to that technology alone will not make the internet space more inclusive; it needs the support of actors ranging from grassroots activists, governments and software developers.

We need new and imaginative ways to imagine the structure of the internet. In these imaginations, language should not be seen as an isolated variable. This qualitative study showed us that even though we set out to study experiences online based on language, language was only a small sliver of the story, which is blended with a variety of other factors, such as internet accessibility, socioeconomic class, etc. Is changing or providing a broader portfolio of languages online (i.e., more datasets and machine-learning support) enough?

Progress toward an inclusive internet can only be made when we recognize the multiplicity and potential of the internet to act as a tool for non-majority languages to flourish in digital landscapes and for average users of all demographics to participate. The internet is an integral part of our daily lives and should be centered around all types of users and their means of access and use.